The relationship between sprinting and a rock-solid physique is why strength coach Erick Minor put together the program in this article. He thinks it’s such a damn shame that so few bodybuilders actually sprint anymore. It’s one of the few fat burning activities that can actually build muscle tissue instead of catabolizing it, and it’s easy to do; just find a track and run! Well, and maybe read this first…

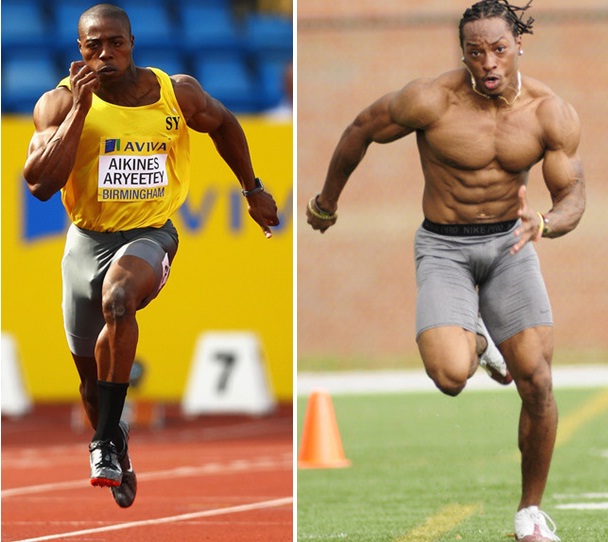

Look around a track and field event sometime and you’ll notice the relationship between sprinters and bodybuilders actually goes both ways, meaning a lot of full-time sprinters also have damn impressive bodies!

Not surprisingly, their training off the track is remarkably similar to that of a hard-lifting bodybuilder.

Okay, quiz time….

What’s the most foolproof way to increase an athlete’s performance?

“Increase his VO2 max?”

Nope.

“Uh, improve one-arm Kettlebell snatch on a Bosu ball performance?”

Hell no.

Well…

The most reliable way to increase any athlete’s performance is to improve his or her strength-to-weight ratio, which is a fancy way of saying minimizing the amount of bodyfat the athlete carries while maintaining or adding lean body mass.

Typically, any athlete with a favorable muscle to fat ratio is likely to have higher relative strength.

High levels of relative strength are necessary in many sports for world-class success. The same rules apply for recreational athletes or guys who just want to look good naked. With the exception of a handful of pure strength sports, a leaner body will perform better and faster, not to mention look better when the clothes come off. So when an athlete or weekend warrior rolls into my facility, how do I go about improving anaerobic performance, maintaining and/or increasing maximal strength, and reducing body fat?

Well, the first thing you have to understand is what I don’t do. Some of you may know that I don’t recommend steady-state “aerobic” exercise for the conditioning of any athlete.

Let me be blunt here:

The only athletes that should perform low intensity cardio such as jogging are distance runners, tri-athletes, or someone needing to lose muscle tissue. Yes, you read right, unless your goal is to have LESS lean muscle mass, the hamster wheel approach to energy system work is not for you. For maximum body composition and anaerobic performance improvements, the modality of choice is sprinting.

A well-designed sprint program will create significant losses of body fat and at the same time increase your anaerobic work capacity and posterior chain development. So less fat, better lungs, and a dead-sexy butt that will make the nymphets and cougars come crawling. What more could you ask for?

The Sprinter’s Body – Nature vs. Nurture

Pound for pound, sprinters are some of the leanest and strongest athletes on the planet. They possess the perfect storm of fast-twitch dominance, exceptional reaction time, great work capacity, and a favorable endocrine profile. Physically, they look pretty damn good too. Now you may suspect that a sprinter’s physical characteristics are all a product of awesome genetics, but that’s only one aspect of the resultant physical outcome. Yes, a certain body type is preferential for success in sprinting, but training, lifestyle, and diet all have a big impact on the expression of physical qualities. To understand my point, just attend a collegiate level track meet and you’ll note that certain track events develop specific physical characteristics in their participants.

For example, even the guy or girl who places dead last in the 200 or 400m sprint will still typically have well developed glutes, hamstrings, and fairly low body fat levels. Even though they may not have what it takes to win even a Junior College track meet, their body resembles that of a world-class athlete. I attribute this to the training.

I Wanna Look Like That!

As a strength coach of some world-class sprinters, I’m often asked if their training regimens would only be of benefit to full time athletes or if the average Joe might reap similar rewards as well. That’s a good question, as it also plays into the Nature vs. Nurture genetics debate mentioned earlier.

So for those who think it’s all genetics and that pro sprinters were born to look and perform the way that they do, check out this training program for one of the top sprinters I train:

The Sprinter’s Body

The following program outlines the typical pre-season training schedule of Darvis “Doc” Patton, #5 ranked 100-meter sprinter of 2009.

(Track workout designed by Monte Stratton, coach of multiple Olympic sprinters.)

- Monday (10am): Track work: speed-endurance (300m, 200m, 100m)

- Monday (2pm): Upper body strength training

- Tuesday (10am): Track work: block starts (2 x 10m, 2 x 20m, 2 x 30m, 1 x 50m) or speed work

- Tuesday (2pm): Lower body quad dominant strength training (squats, knee flexors, hip flexors)

- Wednesday: Soft Tissue therapy/ Massage

- Thursday (10am): Track work: speed day (5 x 60m) or (4 x 90m) or (3 x 120m) w/ 10 minute rest interval

- Thursday (2pm): Upper body strength training

- Friday (10am): Track work: speed endurance (3 x 150m) or (4 x 120m) or (180m, 150m, 120m)

- Friday (2pm): Lower body hip dominant strength training (deadlifts, split squats, hip flexors)

Twice a day workouts, off day restorative sessions, and nary a moment wasted on those minor irritants in life like a JOB? Almost makes you want to be a pro athlete, doesn’t it? (Maybe keep this schedule in mind the next time your know-it-all buddy looks at a chiseled Olympian and snorts, “Genetics” between his endless sets of seated 12 ounce Heineken curls.)

But you’ll be pleased to know that while Olympic hopefuls require a life devoted to training, time-challenged regular folks can experience very significant results with a much more modest training schedule.

…. And the Joes

Now that you’ve seen a glimpse of how a world-class sprinter trains, here’s an abbreviated version that will work for the typical Joe with normal work and family commitments. It may not have you nipping at Doc Patton’s heels in six weeks, but you should expect serious reductions in body fat, increased anaerobic performance, and the beginning development of a smooth gluteal fold that even your long-suffering wife won’t resist slapping.

Training Schedule:

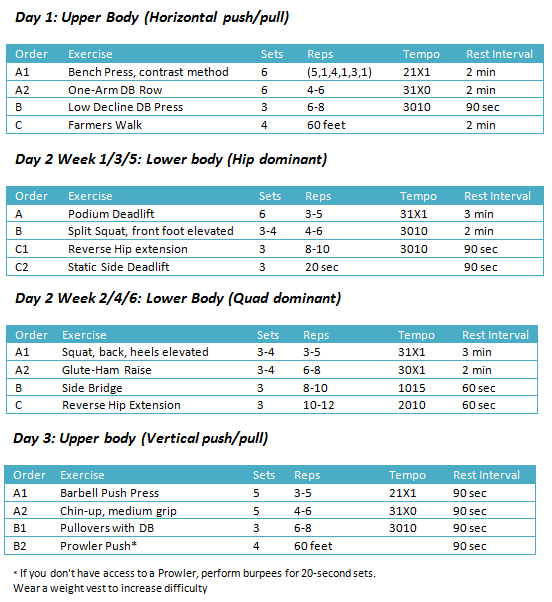

You’ll sprint twice a week, and weight-train three days a week. You’ll perform a heavy maintenance session for legs once per week for the six-week cycle.

- Monday: Upper body: Horizontal push/pull

- Tuesday: Sprints

- Wednesday: Rest

- Thursday: Legs (alternate quad and ham dominant days)

- Friday: Upper Body: Vertical push/pull

- Saturday: Sprints

- Sunday: Rest

Warm-Up and Stretch Descriptions

High Knee March

- Move briskly for about 20 steps, lifting the knees as high as you can with each step.

- Pump your arms.

- Stay on your toes throughout.

Butt Kicks

- Kick your heels up to touch your bum.

- Stay on your toes and pump your arms.

- Works the hamstrings and stretches the quads.

Lateral Shuffle

- Squat down until your thighs are approximately parallel to the floor. Keep the chest up.

- While maintaining this position, quickly shuffle sideway for about 10 steps and immediately return with the same amount of steps.

Cariocas

- Move briskly sideways, crossing the trailing leg in front.

- Uncross the legs and move the trailing leg behind.

- Increase the speed as you get the hang of the footwork.

A-Skips

- Similar to a High Knee March but performed explosively (like a skipping motion with an explosive element).

- Raise kness and pump arms, and dorsiflex foot (lift toe).

- Drive ball of landing foot into the ground.

Active-Assisted Hamstring Stretch

- Lie supine (on your back) with a small rolled-up towel under your low back.

- Actively initiate hip flexion; once you reach the limit of your active range of motion use a strap to deepen the stretch by pulling the leg a few inches farther.

- Hold for 2 seconds; repeat until 6 reps are complete.

- You will feel mild pain in the hamstring on each rep.

- Your non-working leg should be in contact with the floor and completely straight with toe pointing towards ceiling.

- Sets: 3/leg

- Reps: 6 reps (Photos at right)

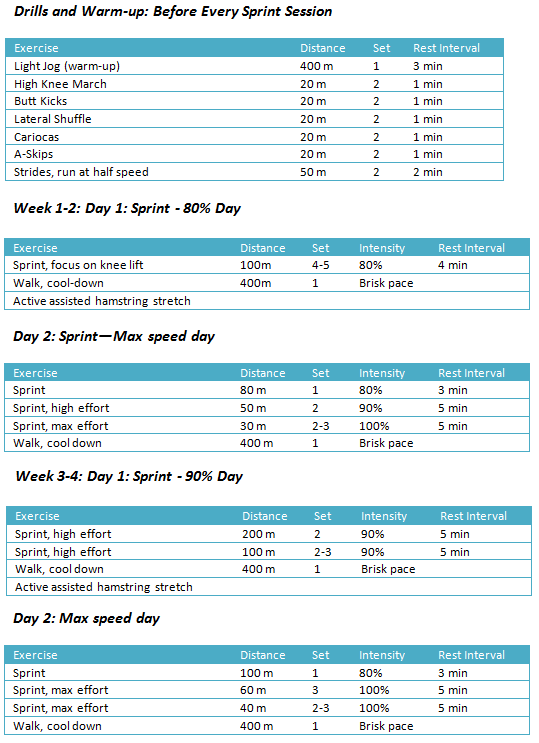

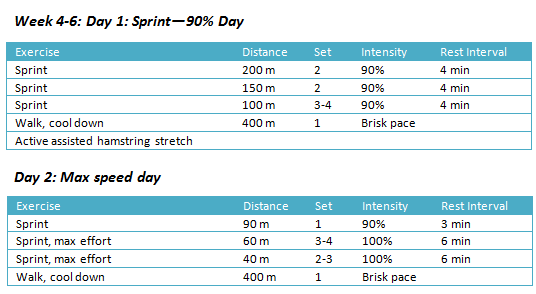

Notes on sprinting workouts

You may notice I don’t recommend any distance over 200 meters. This is because I want you to focus on working within the short term and intermediate energy system (anaerobic alactic and anaerobic lactic system). All sprints should take less than 30 seconds to complete. If you have less than 10% body fat and can’t run 200 meters in less than 30 seconds, you’re in sorry shape, my friend.

Intensity definitions

- When running at 80% you should not feel strained.

- Running at 90% intensity is running at full speed under control. You’re running as fast as you can while maintaining good body position (no arm flailing, neck and face are relaxed).

- Running at 100% requires you to focus on applying as much force to the ground as possible.

- Arm position: arms at 90 degrees, and your hands should pass your pants pockets during each stride.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why should I follow a sprint-based training program?

Here are just a few reasons:

- Increased work capacity

- Increased hamstring and glute development

- Increased maximal strength on all lower body exercises

- Loss of body fat

- Many life & death situations that you might one day find yourself in will require you to sprint. God forbid, if your toddler suddenly starts pedaling his tricycle towards a busy intersection, you won’t be wishing you spent more time on a recumbent bike.

Where I live it’s winter eight months out of the year. Can I replicate this program on my treadmill?

Doubtful. Most treadmills, even the higher end commercial ones found at your neighborhood big box fitness center, won’t cut it — unless you’re dreadfully out of shape. One notable exception would be high-speed Woodway treadmills. But if your facility doesn’t have these, you need access to an indoor facility with a track- or move!

Q: I haven’t sprinted since back when I played high school football. So what do I do? Just, uh, run?

Perfecting sprint form sprinting is much more in depth than many would think and requires years of practice and precise coaching. While most of this is irrelevant to the average guy just trying to sprint his way back into shape, here are a few key points to focus on when sprinting:

- Keep shoulders down and relaxed, with eyes down the track and chin slightly tucked in. Keep your torso erect; don’t lean forward like you’re trying to break Usain Bolt’s record.

- Keep hands relaxed and open, like holding an egg.

- Arms should not cross in front of body; arm motion should be front to back, front to back with hands passing pants pockets on each stride.

Q: The last time I tried sprinting without stretching first I pulled a hamstring. Why do you only have hamstring stretches after the sprint sessions?

Passive stretching doesn’t prevent hamstring pulls. Increasing active range-of-motion and increasing eccentric hamstring strength prevents hamstring pulls.

Q: Should I focus on running faster each workout? Do I try to beat my best time or best distance?

Neither. You will get faster just because you haven’t sprinted in the past. Trainees sprinting for cosmetic purposes (fat loss, glute hamstring hypertrophy) should focus on effort more so than time. A program designed to improve sprint time/performance would be significantly different, including longer rest intervals and start work.

Off to the Track

Getting off the stationary bike and onto the track may seem a little scary to some bodybuilders. Don’t be afraid. Some of the finest built bodies of yesterday and today consider sprinting to be an essential part of their training toolbox. Remember, you have only stubborn body fat to lose and rock-hard quads, hamstrings, and glutes to gain.

Author: Erick Minor

Website: www.erickminor.com

Erick Minor is a freelance writer and the owner of Strength Studio a sports performance and personal training studio located in Fort Worth, Texas.